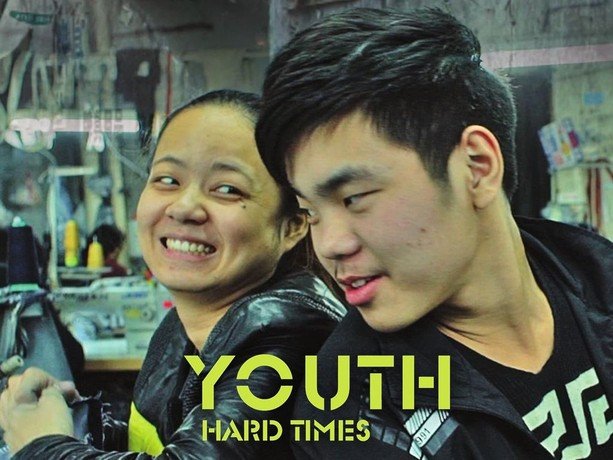

In the rather impressive but baffling four hours of documentary editing, “(Youth Hard Times)” tumbles into chaos depicting the colorful portrayal of Zhili migrant workers who are based in the children’s garment industry. The world has been edited by Wang Bing along with his assistant and CueA editor, Dominique Auvray, in 2015-2019. They recorded nearly ten to fifteen episodes over four years bringing the Zhili township into center and depicting the powerful imagery of migrant workers who seem to be occupants of China.

Through their exceptional editing skills, viewers were exposed to different scenes, immersing them in the reality that at times could and could not be captured through a camera. For the long shoot(15 hours) with the group of 20-year-old workers, Wang captured the 20 hours of footage and then pieced them together, providing a fast-paced tale encapsulating the dispossessed underclass of China within two hours with his assistant. The movie follows a meticulous structure bearing in mind the disillusioned worlds, beginning with stunning and, ending in petty domestic worlds. Wang detonates China with his unrestrained vision and blunt truths through his movies. Profoundly exposing people in China during such historical eras always provides a sense of modesty.

Wang’s workers also come from the outer provinces and possess the same set of skills that his workers have, but according to Wang, they appear Half-cocky and half-doomed. The work they do is not likely to be good enough to sell further outside China, but they know their effort is worth it as they must. The employees of Zhili speak of facts and figures quotas, sizes, and income with such casualness. They understand all too well why their employers offer derisory remuneration rates compared to the volume of denim and Mickey Mouse-patterned clothes that they make over the weekends together with them and in “Youth (Hard Times)” they attempt to do better, too, but this time in terms of their salaries. The outcome is hardly surprising, given the film’s title, but it is still important to understand why Wang’s subjects have to attempt to defend themselves anyway.

Instead of portraying Zhili as a place of mind-numbing work and inescapable sadness, Wang and his group thoroughly examine the moments filled with excitement to figure out how exactly life works for the masses during that particular time in history. For instance, one of the employees (21) is unable to receive payment from an unyielding boss or a nagging wife due to the absence of his earnings book. We witness the explosive results of that fight, where several workers wonder if they will even get paid for what they have done so far. These young people also make fun of each other and get into scuffles during their spare time between trading and worrying about making ends meet, further reminding the audience of their young ages and fast-paced jobs by leaving out bits of their dialogue. At the moment, one of the workers asks her coworker if she could go for a break because she would like to possibly quit, and is told off by her amoral coworkers, “You’re the reason you’re in this situation”.

The most convincing details in both “Youth (Hard Times)” and “Youth (Spring)” can be witnessed in the boundaries of the camera and the mix of layers in the soundtrack.

As they make their way through the bare-bone dorms, staircases, side alleys and workspaces of Zhili, Wang, and Auvray make sure to quietly stalk their subjects and frame them in a nonobvious manner. The ‘slap-shuffle’ made by the flip flops against the concrete floors serves as a great accompaniment to the heated discussions between the workers and their supervisors. One of the most entertaining and thrilling parts of the documentary is the long and partially filmed bid for a pay raise negotiation.

In contrast to the first half of Wang’s trilogy in “Youth (Spring)”, the second half “Youth (Hard Times)” has seemingly much more at stake, and this is why it feels as if more time has passed in the second half. Additionally, there were more moments in the movie’s particular part where Wang Robert’s subjects would look at him for a few seconds through the camera or fidget nervously before talking to him or Auvray. Even though the move sought to be Wanga’s most accessible entry point of the “Youth” series, in all fairness it’s not the most entertaining to watch.

For a start, it may be vital for viewers who haven’t witnessed a Wang Bing film to check out “Bitter Money,” the compelling documentary Wang produced in 2016 intending to demonstrate a proof of concept for what would later develop into the “Youth” trilogy. In any event, do make a point to see ‘Youth (Hard Times)’ to watch Wang and Auvray’s passionate attempt at filming the nauseating but necessary period experienced in Zhili.

You may never shake the feeling that you are trespassing on some reimagined piece of reality, but you may be impressed by just how much effort Wang and Auvray put into their characters. Well, this is the more believable fantasy film, and lest anyone forget, it’s the third part of the trilogy and has a plethora of sentimental details.

Watch free movies on Fmovies.