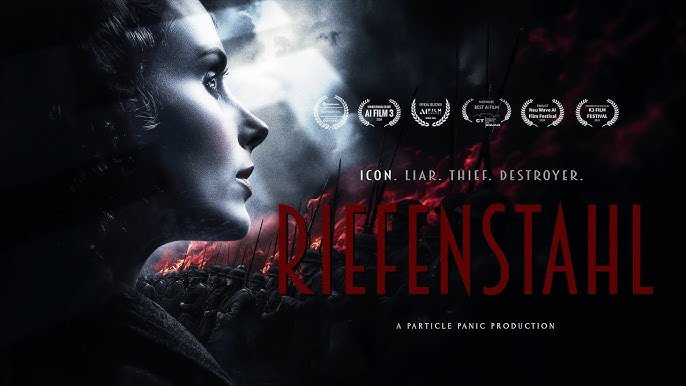

Leni Riefenstahl makes an appearance, albeit distantly, at the Venice Film Festival as a subject in Andres Veiel’s extraordinary deep-dive documentary about the “canceled” artist. This was the Venice of Mussolini’s empire, and in 1938 Riefenstahl was awarded the top prize for Olympia, her stunning and troubling homage to the Berlin Olympics. Her career soared on the Lido and then plummeted straight to hell. Veiel’s film documents her spiraling downfall and the ways she unsuccessfully tried to redeem herself.

Riefenstahl does not come to praise, nor intend to bury the late director. There is no attempt to present a sympathetic narrative, yet neither does it mean to bury her. It acknowledges her as a frontrunner a woman in a man’s world, an artist driven by fierce feminine determination, whose poetry eye and staggering artistry her trademark in Olympia make the entire film a literal (in the case of slow-motion divers and discus throwers) turned upside down work. But it also tries to demonstrate the ways out of which her through line work is and to a degree always will be– intertwined with nazism. Inescapably, defined by it, constructed through it, so that it can never be seen in isolation, not in untouched pristine condition. In protesting the opposite with fury, the directors trapped themselves in an unending masochistic argument.

For the record, Riefenstahl’s defense was that she was an artist and not a politician, a beauty who was compelled to serve, and therefore somewhat foolish in permitting herself to be recruited and employed by Hitler and Goebbels. He claims that “Triumph of the Will,” her 1935 homage to the Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg, was not propaganda, but rather a film “about peace and work.” Furthermore, the body fascism of Olympia was free of racial prejudice, being equally applicable to Jessie Owens as well as the Fuhrer’s Aryan supermen. Art is the opposite of politics, she argues. And moreover, “anyone would have done” what she did at the time. “Should I have been a resistance fighter?” she scoffs to a critic on a 1970s chat show.

Riefenstahl, then, maintained that her claims had no basis in reality and that she was unaware of everything. Evidence suggests otherwise. In her marriage to Jacob Peter, a Nazi sympathizer, and in her enduring “rapport” (as she called it) with Reich minister Albert Speer, there is support for one of Riefenstahl’s claims She appears to have been estranged from much of society during World War II. She ordered the removal of Jewish workers from the set of a film she was making, which could have resulted in a death sentence for them had she not permitted them to be present when she was shooting a street scene. She has always maintained that the Roma prisoners she employed as extras in her 1940 film Lowlands were subsequently released. Roma actually had an entirely different view about it, though. Riefenstahl most certainly ignored any claims of her not having any death camp knowledge, stating. I do not think it is a matter of debate. I want to know how many people died in these war camps, but that is not information I will search for.

Using Riefenstahl’s personal archive footage, audio, and photographs, Veiel examines the narrative that has turned into the story we know now.

He creates an intricate, multi-dimensional portrait that suggests it is nearly conclusive a fragment of sinister history that (metaphorically, artfully) alludes to contemporary unrest. Riefenstahl takes us from the unhappy childhood of the director to her later ethnographic film working with the Nuba of Sudan, a project that she wished would redeem her. However, the film becomes most darkly fascinating when putting her in front of the witnesses who, with shears poised, cut away her defenses amidst a furious cross-examination, accusatory gaze, tempered disdain, and seething outbursts of savage fury.

Riefenstahl died in 2003 at the age of 101. In the last years of her life, she lurked as a wrought, tortured spirit. Her marcelled wig was like something out of a bygone era, and her eyes were alight with fury. She resembled a Nazi-sympathizing Norma Desmond, bellowing that she was still famous; it was merely her horizons that had contracted. I’d always fought as if my life was at stake until I’d got my own way, and what her life was, had remarkably gotten for her, “winning” in her terms, right to the very end, under no circumstances accepting the guilt she brought along for the ride. In her terms, it seemed to be so and maintained to the weathered end. Behind a camera or in the editing room, the director prided herself on selling what in reality was a carefully curated fiction of life. She did things like osmpic, where for propaganda, she defied the rules of nature as well as her own story performing breathtaking magic tricks to the cheers of the Third Reich and reversing the motion of the divers so she could, in effect, levitate them from the waters in a literal grace defying flip. However, in reality, her life was crushed, followed by a thudding back-breaking, uncontrolled laden landing.

To watch more movies visit Fmovies

Also Watch for more movies like: