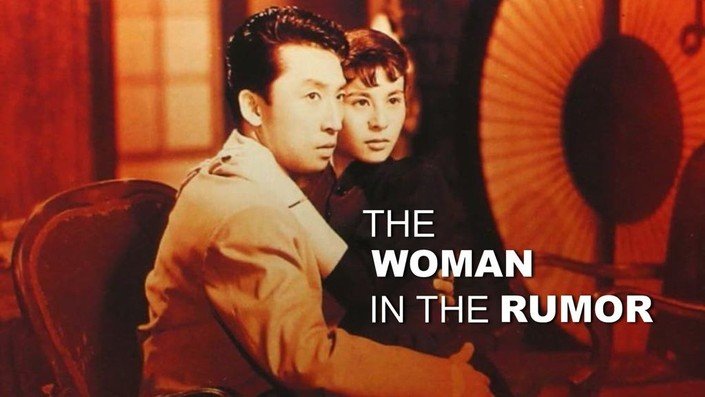

The phrase “It’s a man’s world” originates from somewhere around 1954 and meets Kenji Mizoguchi’s movie “The Woman In The Rumour.” While browsing the movie, it seems like there was a lot of focus on the buffoons and drunks that had no major consequence. Men of power having no one to answer for their deeds is also featured prominently in the film. This leaves Hatsuko, the main character, with very few options. While it is possible to have moderate success running a respectable geisha establishment, the house of Izzats, she still is at the mercy of her customers, who are men. Considering the time frame the film is set in, the business of Geisha houses is beginning to transition into prostitution. In reality, the house that she runs is a brothel.

Business is booming, with loads of loyal customers and new clients stepping in regularly, which is fantastic for Hatsuko. She has been able to support her daughter’s full university education and is also able to comfortably provide a decent standard of living for the 15 girls who work under her supervision. “Initially, I did not quite care and I certainly did hear the rumors people were spreading about me, It was never anything that I found to be fundamentally shameful,” Stated Hatsuko. The men are somehow undisturbed by these conversations. I suppose it does not change their status at work. Sadly the same cannot be said for the women who are involved, let alone those who are just on the periphery of the issue.

Take for instance, the case of Hatsuko’s daughter, Yukiko. She even has a degree, but her husband to be’s family did not let her pursue it and broke the engagement just like that when they found out that her mother was running the Izutsu House. Yukiko, upset with her situation, tries to commit suicide and is subsequently brought back to the Izutsu house to nurse her back to health. This leads to her recovery. Yukiko is not happy with the situation at all because she has some deep seated disdain for the profession and pity for the girls in the house. They are also not exactly happy to see her because they are of the opinion that she is a parasite who feeds on the hard work. Seeing the stark differences in their rooms within the house, you can understand why this is the prevailing thought.

A stylish attribute of the film is how Mizoguchi utilizes space inside the house through the use of straight lines and sharp angles (illustrated by the beautiful geometric shapes and patterns in the title screens). Yukiko is separated from the geisha living, for example, on another floor and eating in her own place. But after a talk with the young house doctor Matoba, she decides to break that separation by moving into their breakfast area to inquire about the sick geisha, and then actually goes into her room to tend to her. The rest of the geishas are in an instant, turned around in their opinion: “We always thought you detested us,” they come out. To which Yukiko replies: “I detest what you do, but I can do nothing about it.”

But there is yet more drama to unfold. Matoba happens to be Hatsuko’s preferred suitor, and she needs him to stay in Kyoto instead of following a bigger opportunity in Tokyo. He begins to appreciate the younger Yukiko’s sweetness exhibited in her interactions with the Geisha. There is a lot to uncover with this plot where they are planning to move to Tokyo and Hatsuko secretly listening to them. The plot is set to rival any of the best melodramas. The acting might not reach the pitch of a Hollywood melodrama, and music is less central to communicating the character’s feeling or intentions, but the emotional weight of the situations is still fully brought to bear. Even if the film is said to be one of Mizoguchi’s lesser attempts (as indeed it was pushed down on him by the studio), he does maintain the tension required for the scenes to work. A performance of Noh theatre serves as the springboard for the confrontation not only does Hatsuko eavesdrop on the young couple’s plans there, but the plays also recite, and even amplify the feeling of the characters.

“It’s all the fault of love,” uttered in one of the plays, reflects an unfortunate aspect (in this case, deafness) which threatens to disrupt Hatsuko’s heart. Towards the end of the performance, a satirical scene pokes fun at an “old woman in the throws of madness” for the audacity of, well, falling in love. While the audience is in stitches, Hatsuko knows that is a direct attack on her.

“Life is just a long series of pain and you have to accept it,” is not an ideal saying to use as a life motto, but as one of the characters in the film said, it serves as a coping machanism. For most of the story characters try to avoid being beholden to any one person, but by the end, one of their main objectives is to steadily try to not having any of the men in their life to rely on. This is no simple task when you are in the business of a brothel, of course. A geisha says at one point: “I sometimes wonder, when will girls like us no longer be required? But they just keep coming one after another.” She scratches her head while looking at the brimming pool of women seeking work. “They just keep coming,” can easily be used while describing male customers too. Seeking pleasure and having power is embedded into their system and unfortunately, I do not have the words to explain how selfish it is to do this at the expense of women.

To watch more movies visit Fmovies.