Peter Five Eight: You, reader — let me be clear, the real you, not the generic one who has always been referred to as the “reader” — how do you find the performance of Kevin Spacey in Michael Zaiko Hall’s Peter Five Eight, an indie crime film released recently? Zaiko Hall recounted to The Independent, “It’s kind of a transgressive act to cast him.” I find myself not really asking this though. My question was about the performance of one actor in the movie, and that is where the problem lies.

“There is a certain comic malevolence,” Hall has said, “a ‘musicality’ to [Spacey’s] character” in this movie Peter Five Eight. This is closer, but still there is a double valance which is at the center of the question, what kind of art is acting. The “comic malevolence” of the role? The “musicality” of the script? Of the actor? For instance, Zaiko Hall points out that the character of Peter is just, “pure Kevin’s style” in Peter Five Eight.

The Independent describes it as a ‘natural fit.’ I am less inclined to imagine however that it is wise to imagine about what, in real life, actors are very much confident about. On the contrary, that which is the comprehension of a certain type of acting performance does include yourself, yes yourself as in person and not as the phrase “ the audience” represents in philosophy.

Spacey has been attending events promoting the film, which is produced by Invincible Entertainment, Peter Five Eight, also called “neo-noir” by some critics. Noir movies, in the 1940s and 1950s, had a special style with a particular treatment with regards to humanity.

The alleys and shady corners in the noir emphasized duplicity, guilt, desire and violence, American life’s vicious id. In this area of genre, in this sphere of writing, I discussed with Spacey that Peter Five Eight relates to Warshow’s well-known essay ‘The Gangster as Tragic Hero written in 1948. I suggest that you read it in advance for Peter Five Eight.

Doing so, I want to ask you what you think: isn’t it better to turn the question, “What do we think about Spacey playing this character,” into something like “How does Spacey envision existing as a character in a morally flawed world, the world of the noir, from the time of such terrifying historical events?” interestingly enough, Warshow cites the optimist ideal built into the life of the United States as part of the social texture—the separation of anti-democracy as relevant to the context, the elites. That is, the Americans would think that such beings do not fit in a democracy.

Tragedy makes one an aristocrat. In The Poetics, Aristotle explains that in order to have the emotions of both pity and fear that lead to catharsis, the tragic character has to be of renowned social status and power, with the phrase ‘if it can happen to him, it can happen to you’ echoing victory. Warshow proceeds to argue that societies run by aristocrats also tend to hold the perspective that human destiny is predetermined, subjected to a higher rational and orderly system that is devoid of any meddlesome politics which could derail human life. This is where Shakespeare fits into the equation. Who gives a hoot actually about what the Labour Corps is going to decide at Richard III?

On the other hand, Warshow argues that Americans themselves even deny aristocracies.

We spend our time in the unrelenting faith that our politics especially make everyone’s life better which is why “It becomes a duty of citizenship to smile.” Which, apparently, is the setting of sitcoms and team-building activities during a corporate offsite event. Even more, we too “have to be on display” of smiles, Warshow claims, as if one has been “drafted in the army in time of war.” What Warshow seems to capture is an authoritarian approach to a story.

“When citizen’s usual condition is emotionally worried”, as Warshow recalls, “somebody’s euphoria is widely present in the sphere of culture as an idiot’s broad grin.” So there is “not much of a difference,” he argues further on, between comedies and feelers where “death and pain are provided as mere background of elevated view.” It is the very equivalent of any popular psychosexual theories and corporate ideologies they also in totality boil down to wonkish fantasy.

So why is it that you still have wants that remain unfulfilled? Why would one want to sit through those antagonistic protagonists, suffering victims or antiheroes of film noir? Spacey explained, as he was quoted, “Quite often, in spite of the moral judgement of the audience, that audience wants the antihero to succeed.” When it comes to Spacey’s work as an American actor, we could say that the film problem is that of American Beauty’s.

Suburban optimism images – ‘cut away places with weary real estate agents and undisclosed problems’ plus ‘a neighborhood that exists in an unreality’ – makes sense only within parameters of extreme falseness and mental health issues. Spacey observes that, “there’s a very fundamental safety” a community who break the laws, who are the misfits and in Spacey’s view, politicians are even “worse.”

Warshow goes on to assert that American’s narrative-language itself disapproves of “the organization and reasoning of obsession,” which makes its characters free from abnormalities or corruption. In such circumstances, even “an evil society” like the dirty fictionalized film city lightens the lifeless and mundane strokes of modern townism. He is the antithesis of progress, pure determinism which baffles most people and society in general. Maybe he is basically “what we want to be and what we are scared potentially of being.”

The film noir anti-hero isn’t in this possible predicament where a lot of the patterns around being worshipped and reviled are very similar.

This explains what Warshow calls the gangster film’s ‘tragedy’ and ‘tremendous completeness’ in the depiction of time. To Spacey, it seems to show the connection with the Shakespearean era. “This idea of

self conscious antiheroes,” he muses, “is sort of a Shakespearean device he introduced for Richard the Third, where the actor speaks directly to the audience.” In other words, we cease to be passive observers and begin to share the guilt as active participants.

“I had the chance of playing Richard the third across several continents before I ventured into House of Cards,” Spacey narrates, “which isalso rather noirish, and builds over the Shakespearean devices of asides. You see people beginning to empathize with Richard but not before the shock of his murdering the children in the tower. You have these anti-heroic personalities who remain introspective of their environment while the audience is actually thinking along with the character.”

The quest for noir antiheroine is worth pursuing because it points towards another vision of the world, one that the believes in the ‘happy outlook on humanity’ will dismiss. Disguised within the narrative, Shakespeare’s Richard as a noir figure is not at all sinister for the American audience because he indulges in a higher volume of mass murder. He kills, just much more efficiently And on a smaller scale compared to the ‘joyful’ contemporary nations.

He is tragic because he wants more from his existence than what the fate is willing to grant him – more proper regal authority, more territory to his name, more history, another centre of power. “The gangster’s whole life,” Warshow writes, “is, in essence, a struggle for distinctiveness, for the extraction from the crowd; and he never stands from the large mass because he is an individual” in Peter Five Eight.

But the fear of why stepping away from joyfully watching and playing along with the antihero character is a dread to shake fans engaging with Stewart’s “intellectual possibility of an alternate universe, in which those ‘imagined being’ were within the depth of want.” It is that the whole once pleasant civil environment of one’s common happy citizenship starts to have the effects of that film noir.

“It’s an interesting genre,” Spacey notes, “because if you think about it, it is spread across many films that you wouldn’t imagine it being. Like The Great McGinty, a movie written and directed by Preston Sturgis, an artist who was later known for screwball, tells the story of gangsters, poverty and a guy who chooses to be happy in the end. Which is the most astonishing.” Is happiness so hard? Looking at Spacey, he asked, ‘Popular no. of movies dealing with this and noir. Charlie Chaplin character.’

He was a small fellow who always managed to find trouble and escape from it as well. Before he made all that, Charlie explained, “I just need a park, a cop, a girl and a dog.” The film finished with him leaving, on to another of his “sunrise” adventures, whether he has won or lost.

For the Tramp of Chaplin, another sunrise, another horse for Richard – to say only one thing about the transgression of noir genre. If we wish to behave as model citizens we have to thwart the urge to recall the fact that wish or desire invariably brings us to ‘that time’. Noir is the genre that prefers flashback structure. In some sense, as with Spacey’s character, there is no possibility of an ex-cop leaving the police station any other way than being ‘in the flesh’.

Insufficient recollection such as this one ultimately frustrates the work of investigative detectives: “Take Double Indemnity,” Spacey is speaking now – “You’ve got a scream as a gorgeous woman who spins around in some idiot’s web. It’s about ‘Oh what a stupid thing I did to let myself be trapped’.” But is it not also true that life was more exciting when you were younger? Memory is a universal embarrassment, a social blunder that no one wants to be associated with, but one that noir glorifies – cruelty, carelessness, darkness: perfect.

It can be described as a psychological form of self-gangsterism where one speaks to their past self. Warshow’s description of filmic voyeurism applies here: “We can take pleasure in its sadism, not only because we view it from the lenses of a victim, but also because the victim is the gangster.”

Flora and Gozalets (N.D.) suggest real connection can be replaced by a sense of simple consolation, and community by a lively cosmopolitan, therapeutic “Americanism.” The cinematic gangster can’t afford to take this perspective. It is not that he is a criminal; it is that he is an artist. It is a crime in itself to be obliged to win. All means are a crime in the complex depths of modern consciousness. Succeeding is considered a crime, making one an isolated figure in a fierce world.

Spacey portrays Vincent as a Hollywood cop selling celebrity crimes to Hush-Hush Magazine amply demonstrates the idea. Spacey’s Vincennes exists in the threshold between cheap gangstahood and celebrity’s involuntary lust to watch, being the antihero but also a voyeur. For Jack, being on the breadline for Hush-Hush and bringing dirt of the LAPD to the surface are two iconoclasms that are equally harsh and shouldn’t exist in the first place.

In this way, the story leaves him the only survivor in the midst of his foes. ‘In the movie Peter Five Eight, Spacey remembers, ‘Everyone was getting shot and dropping out. ‘I wished the chair to be pushed back and fastened so that when he got shot, there was no place left for him to run.’ Spacey says while emphasizing that it was the use of image that filled the big galley. It’s how we love to be spoken to in noir: violence is its most beloved exclamation, though it is typically simulated politeness toward us.

Much like how an actor presumes the character of Richard, a gangster in a film noir can only move into a specific direction and that direction is towards you. Spacey explains “when I did it in House of cards, I would do that sort of thing only once, where I would address the audience to include them in the scene, when I was used to addressing the camera lens where I only saw myself. I did not like that and so I would pretend to be talking to one person, my friend.” This may explain why only formalist debates on noir box the readers into deathly dullness. It may also be why however much such transgressive work is condoned, it is always invited with a barrage of immoral unscreaves.

In noir, an audience’s involvement spans both sympathy and contempt, and this relationship is considered as short-term duration in Peter Five Eight. How would you have enjoyed reading Hush-Hush if it were set in the Golden- Age of Hollywood? Would it have turned the reader into a partner in crime with Lana Turner? Would she have made you see to consider yourself greater than her? What could you say about Jack Viscenses from L.A. Confidential? Do you sympathize with him when he dies? Do you feel he earned his end? Has his death changed your opinion about him for the better?

“When we were shooting the ‘She is Lana Turner’ scene,’ Spacey said, ‘I was talking to Curtis Hanson, the director of the scene, who cast Jack Vincennes for the film, who he would cast if it was really 1952? I am sure he had someone like Spencer Tracy or William Holden in mind.”

‘Dean Martin,’ said Curtis. Dean Martin? ‘Go watch Rio Bravo,’ he said. Due consideration. Rio Bravo definitely has a certain noir quality to it. I view it and it’s as though I see a figure that can no longer stay in the position society expects him to be in, who understands that he must evolve and this evolution will be painful.” For you, does the sight seem pleasant?

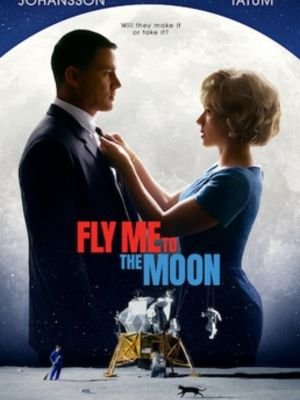

Watch free movies like Peter Five Eight on Fmovies